The Grand Undermining Lie Of ‘Asking For More’

“Women are asking for raises as much as men, they’re just not getting them.”

That was that the damning conclusion of a May 2018 study on salary negotiation. And that was also the gist of the slew of global headlines that followed. But nine months later, these headlines are no match for the wave of long-held feminist workplace discourse—in the media, in books, and in brand marketing—that continueks to put the onus on the individual female-identifying employee to “lean in” and get that raise. If only it were that easy.

The first decade of the 21st century was all about asking for more; women deserve, and should demand higher salaries and better opportunities, the prevailing wisdom said. And at first blush, that sounds right. We do deserve more. We should demand it. This idea was supported by the 2003 publication of the influential and rigorous Women Don’t Ask by Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever.

At that time, Sheryl Sandberg was already well into her tenure as Google’s VP of Global Online Sales & Operations, observing some of the foundational inequities that formed her thinking on the topic.

Seven years later, Sandberg’s TED Talk on “why we have too few women leaders” received millions of views and led to the book that quickly came to dominate the feminist conversation around equality in the workplace, Lean In. “Women are asking, the research says. Any myths about women’s unwillingness to advocate for themselves are just that; myths that don’t address the real problem.” The popular narrative went like this: Women are holding themselves back from their own greatness. If one doesn’t step up and negotiate an equitable salary, how can one expect the gender wage gap to close?

The problem with this line of thinking, according to the findings of a 2018 study, is that this story simply doesn’t hold true anymore. Things have changed—but they haven’t necessarily gotten better. In the decade following Women Don’t Ask, women are asking, the research says. Any myths about women’s unwillingness to advocate for themselves are just that; myths that don’t address the real problem. And yet, the same wave of personal responsibility and individualised self-improvement keeps crashing on our heads. Why TF is that?

Dr. Amanda Goodall, senior lecturer at Cass Business School of the University of London, is the first to admit the results of her aforementioned 2018 study were surprising. “Absolutely, fundamentally, no. We didn’t expect this.” But holding background factors constant, their control groups—polled in Australia, where the breadth of the pay gap and amount of women and men in leadership positions is close to on par with the US—showed that women asked for raises just as often as men, but men were five percent more likely to be successful. A modest difference that presumably adds up over a lifetime of successful salary negotiations and appropriately masculine handshake-hugs.” The study also found no evidence to suggest that women had a reluctance to ask for a raise for fear of upsetting their boss—or due to low self-belief, as many people (and many career advice books) might assume.

For associate professor Catherine Rottenberg of the University of Nottingham, and an expert in neoliberal feminism, Goodall and team’s results point to one key takeaway: Women cannot be blamed for the pay gap. While the battle for a fair salary is tasked to the single individual to wage, the war of systemic sexism and workplace gender expectations is the backdrop. And we have no reinforcements to fight with. No institutional strongholds to speak of. Just a lot of “Go get’ em girl!” and “Who run the world?” Michelle Obama made a December 2018 Brooklyn audience gasp—perhaps with personal identification as much as from the shock of hearing a First Lady swear—when she referred to the rhetoric of the “lean in” project as “a lie.”

“I tell women that whole ‘you can have it all’—mmm, nope, not at the same time, that’s a lie,” she said. “It’s not always enough to lean in because that shit doesn’t work.” “She’s right you know,” tweeted a reader. “There was a generation of us who were told we could have it all and felt somewhat a failure when we knew we couldn’t. Thanks for validating what we knew all along, Michelle.”

“The popular “lean in,” hyper-individualized discourse “is all about internalizing the revolution,” says Rottenberg. But that was far from the first time “lean in” culture was publicly questioned. In a widely-read 2012 Atlantic essay, Anne-Marie Slaughter, a Princeton dean and former director of policy planning at the Department of State (now-CEO and president at New America) summed up her criticisms of Sandberg’s TED schtick by saying: “When a woman starts thinking about having children, Sandberg said, ‘she doesn’t raise her hand anymore … she starts leaning back.’ Although couched in terms of encouragement, Sandberg’s exhortation contains more than a note of reproach. We who have made it to the top, or are striving to get there, are essentially saying to the women in the generation behind us: ‘What’s the matter with you?'”

And then there’s journalist Katherine Goldstein’s take as a former Lean In superfan. “The manifesto felt like a cross between a playbook and a bible,” she wrote last December. “I now believe the greatest lie of Lean In is its underlying message that most companies and bosses are ultimately benevolent, that hard work is rewarded, that if women shed the straitjacket of self-doubt, a meritocratic world awaits us.” But as academic research suggests—as if it wasn’t obvious for women on the level of lived experience—that merit-based reward system is a myth.

Put simply, that’s because sexism, like race and class, is the same as it ever was. “Women’s so-called worth in the public sphere is still not perceived to be equal to men’s,” says Rottenberg. “Although this has been progressively weakening … the assumption is that women are either not the primary wage earner or that they are simply worth less on the market.” Further, she points to Shani Orgad, associate professor at the London School of Economics & Political Science, who recently released a book that says the idea that a woman’s primary role is to be a mother persists in both US and UK culture—from advertisements to policy making.

The popular “lean in,” hyper-individualized discourse “is all about internalizing the revolution, and precisely does not address systemic solutions,” says Rottenberg. “[It] incites women to take full responsibility for their own well-being and self-care. This discourse ultimately disavows the structural injustices that shape our lives. Women who fail to live up to the new ‘lean in’ ideal of successful womanhood are deemed failures, even though we all know that the playing field is grotesquely unlevel to begin with.”

In Fortune late last year, Lean In president Rachel Thomas herself explained that Sandberg’s work had been largely mischaracterized ever since the book shot to the top of the charts. “One of the strengths of Lean In is the title, so catchy it instantly became part of the lexicon,” she writes. “But that strength is also a weakness. In the six years since the book came out, the phrase ‘lean in’ has been used to mean many things—some of them very far from what Sheryl [sic] intended.”

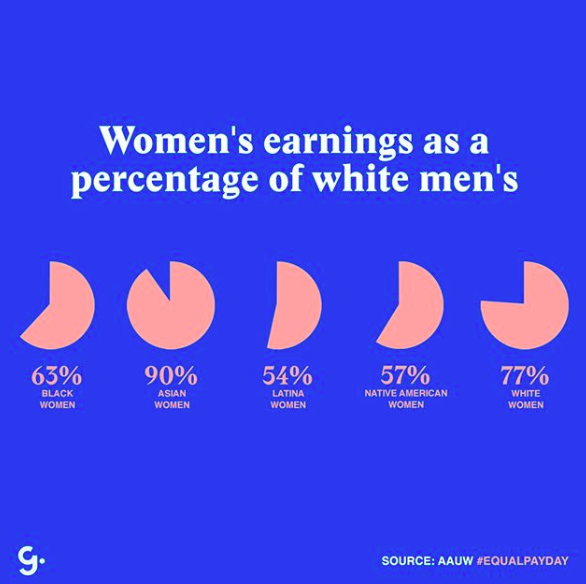

Regardless of the source (or sources, legion), popular belief that puts the burden on singular women—many of whom are already fighting on the hugely uneven hill of race and class—means emphasizing our human capital and minimizing both the nature—and scale—of what we’re up against, as well as the stakes.

Rottenberg agrees: “The solutions [the ‘lean in’ conversation] posits ultimately elide the structural and economic undergirding of these phenomena, rendering the plight of poor and immigrant women, as well as women of color, even more precarious and invisible than they already are. In this way … it helps to reify white and class privilege as well as heteronormativity, lending itself to neo-conservative and xenophobic agendas.”

Then there’s this study. A December 2018 paper published by Duke University researchers in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology measured the effects of “lean in” narratives on women’s sense of personal responsibility. They found that those were read or listened to these “DIY messages” saw an uptick in their self-belief when it came to their ability to solve problems and get ahead at work. A somewhat sunny-sounding result contrasted by another bleaker one: The same participants were also more likely to believe that women were not only to blame for not improving their poor situation in the workplace, but for causing it.

“When you individualize the problem—and place the burden on women—then when they don’t succeed, it is somehow their fault,” says Dr. Deborah Kolb, the author of Negotiating At Work. That could be seen as part of the “social cost” of asking; one that belies the double bind of self-negotiations.

“Women often are expected to demonstrate a high degree of concern for others and may pay a social price when they do not,” Kolb says, pointing to further research. The inference being that advocating for oneself is something of a gendered transgression for working women, even today as the message of “lean in” still reigns. And in isolation, self-advocating is no guarantee of a high salary. And “no shit,” say the women reading this.

For millennials women, another social cost of the current set-up could be an unwillingness to change jobs, even if they’re not satisfied. Goodall’s current research suggests that while women used to leave jobs more regularly than men, women under 40 are now less likely to leave a job if their job satisfaction decreases. While the reason for that isn’t clear to researchers, many young people might immediately refer to soul-crushing debt as one potential factor.

However bright the future may or may not be, personal as well as collective change is how we’ll navigate it.

“When you negotiate over these issues, it can pave the way for others to negotiate,” says Kolb, adding “I think the focus on just salary is a problem. You need to negotiate for what will make you successful—the terms and the conditions of your role.”

“Think about a common negotiation situation where a woman thinks she is the right person for a role but her boss is likely to select someone he knows well—what we call ‘hire like me,’” she adds. “If the woman negotiates with her boss about the criteria for the role, she can help shift the negotiation and put herself in a better position.”

According to Goodall, 70 percent of workers think they deserve a raise, and not getting one can be extremely detrimental to one’s confidence and future performance. So when it comes to actually trying to get one, consider the timing and “try to minimize the negative impacts,” she says. “Do as much background and homework as you can to know ultimately whether you really feel that you are right for a promotion or raise. Minimize the chances of not getting it.”

And of course, the remaining piece goes beyond negotiation advice. “We urgently need to begin implementing progressive structural changes,” says Rottenberg. “Things like guaranteed paid maternity and parental leave, free public, quality child care, and ensuring a living wage with decent working conditions for domestic and care workers.”

But considering the state of things, that may be the bare minimum of what’s missing. “We will need to become even more daring, creating coalitions and unexpected alliances,” she says. “Institutional infrastructure and support are vital not only for buttressing us against … neoliberalism, but also—ultimately—for ensuring that the conditions under which vulnerability and interdependency are produced can be distributed equally.”

That means ~leaning into~ civic life, and holding the companies and institutions that hire us—as well as govern us—accountable for our unequal salaries as well as our opportunities. Not yours or mine, but everyone’s.

Originally published on Girlboss